Complimentary Story

By Clifford ReevesEditor’s Note: Clifford Reeves passed away April 6, 2015 at age 89. The following memoirs were read during his funeral service, a poignant reminder of that “Greatest Generation” of American heroes.

My military experience began at Great Lakes Naval Training Station, and went as follows...

After being logged in and given a serial number that would be our permanent identification number, we were immediately sent to get our first haircut. The barbers were friendly and asked what kind of a cut we would like -- after they ran the clippers down the center of our heads.

Next we were assembled in a large room where we were told to take off all our civilian clothes that we arrived in and put them in a box to send them home in. There we were, naked as a jay bird, when the commanding officer told us to line up for a physical, and I mean physical.

They checked places I didn’t even know I had. After that we were issued our Navy uniforms. From our skivvies right on up to our Navy coat that was called a pea coat. I am still trying to figure out why they called it that. Later on when we were in combat, some got so scared they wet their pants but their pea coats stayed dry. They also gave us a large canvas bag that was called a seabag, to put our clothes in and a much smaller bar bag for our personal gear, such as soap, razor, tooth paste and so on. This they called a dittie bag.

Later that same day we were assigned to our barracks and met the Chief Petty Officer that would transform us from land lubbers to seamen. The first thing he told us was to forget our first names. Everyone was called by their last name and the title “Mr.” was a thing of the past for us, but when you talk to an officer you better remember to say “Mr.” to him or get ready to do extra duty. I know that we were still in the United States, but the language sure became foreign.

The Chief assigned us to bunks that were three high. When he called our names he would say “your bunk is on the starboard side” or “on the port side” of the building. Then he said to put our gear in the lockers that were along the bulkhead, “That’s ‘wall’ to you landlubbers.” The doors became hatches, the ceiling was the overhead, the halls were companion ways. Don’t ask me why but the toilet area was called the “head.”

I thought if I joined the Navy I would not have to march and do close order drills like the army -- makes sense doesn’t it? Wrong! We marched on the drill fields, we marched to the mess hall, we marched to the rifle range and where ever they wanted us to go. I might add that many of the drills were in double time. I don’t know what the hurry was because we always had to stand and wait after arrival.

Those of us who survived boot camp went on to serve in the regular Navy and were placed where ever the greatest need was at the time. I was sent to Norfolk, Virginia for combat training -- you know, climbing walls, running obstacle courses under fire, crawling on your stomach through a muddy field with miles of barbed wire everywhere. (Crawling under barbed wire really teaches you to stay low).

Now we were ready to man the ships and go into combat. Since we were already in Norfolk, Virginia, which is one of the largest United States seaports in operation, you would think we would board a ship in that harbor, right? Wrong! What we boarded was a train that took us to Evansville, Indiana. Evansville, as it turned out, is right on the bank of the Ohio River. Our government felt that in case of an enemy attack, it would be safer to build some of our ships inland, and since all of our landing crafts had flat bottoms instead of V shaped keels like the rest of the ships, we were able to navigate down the Ohio river to where it joins the Mississippi river, then all the way down the mighty Mississip to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico.

To keep the ship light so we could float down the rather shallow rivers, we waited until we went to Pensacola, Florida to install to install our mast and armament.

The ship that I was on is called an LST. LST is short for Landing Ship Tank. After the gun turrets were installed and we took on tons of ammo and supplies, we got underway for Norfolk, Virginia again, where we loaded our food and fresh water for our trip across the Atlantic. The tank deck was fully loaded with half-tracks, tanks, trucks and military hardware. The last piece of equipment that was loaded was an LCT, “Landing Craft Tank.”

Not only were we carrying an LCT, on the deck, on our Davits we carried small boats known as LCVPs, “Landing Craft Vehicle & Personnel.” The LCVP was our ship-to-shore transportation as well as a vehicle to transport troops to the beaches. Each LCVP could accommodate 50 troops as well as the crew of three.

At last we were underway to help defend our loved ones and the home of the brave and free. After our trip down the rivers to the gulf and around the tip of Florida to Norfolk, Virginia we felt like we were seasoned seamen by now, right? Wrong!

There is no word in the dictionary to say just how sick you can get when your ship starts to rock from side to side while the bow of the ship rises and falls with the swells of the mighty Atlantic Ocean. I think the ocean became much higher as our crew leaned over the side and tossed up our last meals. I was never so sick in my life. Naturally when everyone is that sick, the commanding officer lets you hit the sack until you get well, right? Wrong! Guess what happened next! We were told to get a pail and carry it with us so we would not make a mess on the deck. I think I nearly died two or three times that day, but to my surprise, I got well and that was the last time I was seasick. Some of my buddies weren’t so lucky. Every time we were in a storm and experienced high seas, they would get sick all over again. Some put their name on their pail and kept it handy.

Well, because we traveled many extra miles dodging submarines and mines that were placed in the sea lanes, and our top speed was 12 knots per hour, it took us 22 days to cross the Atlantic and tie up to the pier in Scotland. Incidentally, a “knot” is 796 feet longer than a mile. A knot is 6,076 feet, compared to a mile at 5,280 feet.

We unloaded the LCT and some of the supplies we had on board and headed for Bizerte in North Africa. To get there we had to go through the Strait of Gibraltar. The Strait is a narrow body of water between Africa and Spain. This Strait had so many man-made hazards that we had to have a naval pilot aboard to get us through the mine fields and the huge nets that were anchored in the Strait so that enemy submarines could not get through and wreak havoc on the ships in the Mediterranean Sea. When we unloaded our military hardware, we loaded all of the Arab soldiers that we could carry and headed back to the British Isles to prepare for the invasion of Normandy France.

While we were in the Mediterranean Sea, we experienced many close calls from enemy aircraft fire and floating mines. Little did we know what awaited us when we set sail to make our assault on the coast of France.

At this point, let me bring you up to date on my personal responsibility when we were engaged with the enemy. When enemy aircraft or subs were a threat to us, the officer on deck or the duty officer would sound “General Quarters.” When the warning was sounded, we immediately went to our pre-assigned battle stations. Because our crew was relatively small, all non-officers were assigned to battle stations. I was assigned to a 40 millimeter anti-aircraft weapon. It took four men to operate the weapon. One would raise and lower the barrel while seated on one side of the gun as another man would rotate the turret back and forth with hand cranks that were located on either side of the gun. As the shells were fired, one man took pre-loaded clips from a ready box behind the gun and handed them to a fourth man that was standing on a platform at the rear of the turret. He then fed the shells into the loading breach so there was a continuity of firepower.

All through the war, from the time I boarded the ship, my station was on a 40 millimeter gun. We worked as a team and became quite efficient. Can you imagine my surprise when the Gunnery officer came to me before the invasion and told me to leave my position on the 40 millimeter in the bow of the ship and go aft to the 20 millimeter located near the stern of the ship?

I argued with him, saying that we belonged together and that we operated as a team. His next question was right to the point. He asked, “Can you do as well on the 20 millimeter?” -- when I said “no,” he said, “that’s why I want you to go back there so you can work either one with equal skill.” He went on to say that he was not asking me, he was telling me. So I reluctantly followed his orders.

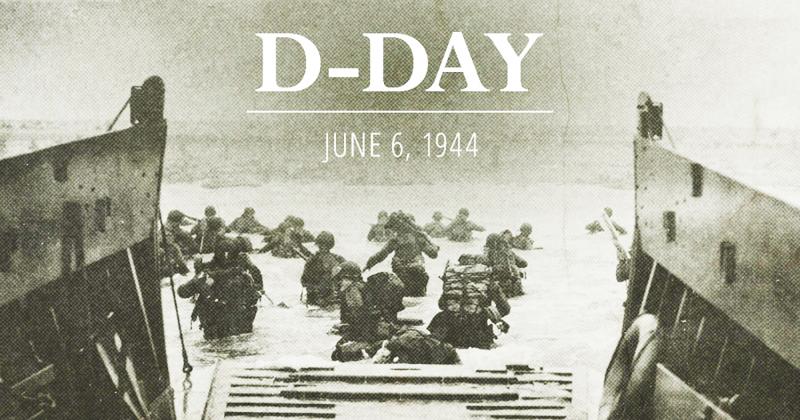

D-Day (June 6, 1944) -- In the dark of the night, we took our position in the convoy and started across the English Channel. It was no surprise to the Germans that we were coming, because they were shelling us with long-range cannons from the coast of France. Planes were dropping flares to light up our convoy so their planes could bomb and strafe us. We, in turn, were shooting tracer projectiles that allowed us to see the line of fire so we could follow the tracers visibly and be guided to the target. The sky was lit up like the fourth of July. What happened next is a memory that I will carry to my grave...

From my position on the fantail of the ship, I saw a torpedo coming toward the stern of the ship where I was stationed. That torpedo missed us by inches. Suddenly another torpedo came directly at us and struck the ship with such force that the ship literally jumped in the water from the explosion. The torpedo hit right below the gun turret where I had been stationed prior to my transfer to the gun I now operated near the stern of the ship. Every man in that turret was killed including the man that took my place.

Why was I spared? I don’t know, but you can be sure that I thanked God for my safety, and still do. The water tender pumped the water out of the bilges on the forward starboard side and filled the bilges on the port side from midship aft. This brought the jagged edges of the twelve-foot-diameter hole above the water and we continued on to make the invasion.

It was early morning when we dropped anchor about 600 yards from shore. We immediately lowered our small boats and hung a large rope ladder over the side of the ship so the soldiers that were on board could get into the LCVPs. When we had ship-to-shore duty, I was one of the crew that was in the boat taking the soldiers onto the beach. Picture in your mind, if you can, a series of ramps that were placed in the water at low tide. When the tide came in, it covered the ramps with water so you could not see them. Along with the ramps the water was strewn with barbed wire and if that wasn’t enough, the beach was heavily mined.

When our craft pulled onto the beach as far as we could, we dropped our ramp so the soldiers could go ashore. Just as the soldiers left our boat another boat pulled in and slid up on a mine. Nothing can adequately tell of the horror of that moment. Men were flying through the air, shrapnel from the boat and exploding ammo that was in the boat was bouncing off the side of our boat. Many of the men that were blown sky-high came down in pieces. Many of the men that we dropped on the beach were killed or wounded.

The enemy was back several yards from the beach waiting for our arrival, and as we came in bullets were flying everywhere, many hitting our boat. We were instructed to offload our men and get back to the ship as soon as possible so we could bring in another load. As you can imagine, when we were leaving the beach to get more soldiers, some of the wounded men were hanging onto the boat begging us to take them back. Before we went in with the first load, we were told not to bring back any of the wounded until the beach was secured. If each boat stopped to load casualties, we could lose the beach head.

Friends, I pray to God that you will never experience the horror of seeing people bobbing in the water dead that were alive when you left them. The movies try to glamorize war and portray macho heroes, but I am here to tell you it is a living hell and there is no glory in killing, or seeing men killed or horribly wounded.

When the beach was finally secured, our ship came onto the beach to unload the tanks and trucks that were loaded with supplies and food. Our ship stayed on the beach all the rest of the day until high tide came in and we could leave. All the time we were on the beach we were loading soldiers onto stretchers and taking them aboard the ship so the doctors that came with us “to care for the wounded” could tend to their needs.

While I was on the beach, I found four rifles and took them with me. When the tide came in and we went back to the main ship with our LCVP, I stored them under my mattress. The next day while I was standing watch, the officer of the day came and confiscated the rifles -- so they would be “in a safe place” until we got back the good old USA. That was nice of them, right? Wrong. I never saw the rifles again.

At last we were headed to London, England. You will never know what a thrill it was when we saw the White Cliffs of Dover and pulled into a dry-dock in London to get our ship repaired. No, we weren’t out of danger, because the Germans were sending buzz bombs and V2 rockets into London. What, you ask, is a “buzz bomb?” The Germans built and launched the first unmanned flying missile. They were crude bombs with wings that were placed on a ramp pointed at London England. The fuel was measured so the bomb would reach London, and when the fuel ran out the bomb would go into a glide and would drop on anything that was below it. Yes, it could be a school, hospital, a store or a factory. It did not make any difference to the Germans.

It took a month to repair our ship because when they built it in the USA it was welded from stem to stern. The English were not equipped to weld the new plates on so they riveted them in place. Whenever any enemy planes or robot bombs would come, the sirens would sound a warning so the workers could go to a nearby bomb shelter to take cover until the “all clear” sounded.

The engines of the buzz bombs were not muffled and you could hear them a long way off. When the engines shut down, you knew the bomb was coming down and we would watch the missile to see if we were in danger. The buzz bombs would glide for about a half of a mile on their descent so we could see what direction it was going. If it was heading towards us we would take cover in a building or a bomb shelter.

There were a lot of make-shift bomb shelters in London. Once, when I was walking down the street in London, a bomb struck a building on the top floor above me. I was fortunate in that there was an unlocked door that I could enter and get protection from the bomb. I should mention that buzz bombs left a trail of fire from their engines and it was easy to tell when they were coming down, no fire trail and no engine sound, actually it was easier to tell where they were at night because of the flame.

Well the English engineers said the ship was ready to sail after about a month in dry-dock so we took the ship on a shake-down cruise to see if she was sea worthy. The ship began to take on water because some of the plates were not tight enough to secure water-tight integrity. We pulled back into dry-dock, decommissioned the ship and gave it to the English.

There we were in England without a ship, so they loaded us aboard a liberty ship to take us home so we could be reassigned to another ship. I was shocked when I was assigned to a battleship, the “USS Arkansas.” It was known as the “Grand Old Lady” of the navy because it was the oldest ship of the fleet. We headed out in the mighty Pacific Ocean on our way to the Hawaiian Islands, but while aboard the Arkansas, my tour of duty expired and I was taken to Shoemaker, California for discharge.

I should mention that many of the navy’s oldest ships, and some that were not so old, were later sent to a location in the Pacific for what is referred to as the Bikini Atoll bomb test. They dropped an atomic bomb over the ships to see how many the bomb would sink. As I recall, all of the ships sank... except -- you guessed it -- the Grand Old Lady of the fleet, the USS Arkansas.

I could mention some of the air raids and mine fields that we encountered, but I won’t. Suffice it to say that I am here because God loved me enough to bring me home safely. I am a living testimony of His great love and concern.

Thank you dear God! I remain yours in Christ Jesus, who gave His life so that we may spend eternity where there is no more war or dying. May God bless you all until we meet again in the clouds with Him.